Wartime Trading

First World War: food supply & shortages

As soon as war was declared in 1914, Sainsbury’s posted notices in the windows of all its branches stating that regular customers would be kept supplied and warning against hoarding. Despite this appeal, queues began to form as worried customers stocked up on basic foodstuffs.

Panic buying quickly pushed up the prices of imported provisions, particularly sugar and butter. Regulations were put in place: managers were instructed not to sell more than 2lbs of sugar to anyone. The pre-war incentive schemes offering gifts of china, cutlery or table linen with purchases of sugar were also suspended.

Luckily, good relationships with UK suppliers such as Lloyd Maunder and Frank Sainsbury meant that some ‘home-produced’ food could still be obtained at reasonable prices. With the rising price of imported butter, margarine became an important product during these war years.

Sainsbury’s ran a huge advertising campaign to encourage people to switch to its own-brand margarine Crelos, describing it as ‘the most delicious, digestible and economic form of fat food you can buy.’

However, even if goods were available, the requisitioning of delivery horses by the army affected distribution to the branches. Home delivery services in some areas were also stopped and customers were asked to carry smaller parcels home for themselves. They were also encouraged to settle their accounts promptly. John Benjamin Sainsbury wrote to managers:

‘I have to pay cash for all goods, and must ask my customers to do likewise.’

Rationing during the First World War

In October 1917, a government scheme for the distribution of sugar was introduced. Customers were required to register at a particular shop, and the number of registered shoppers determined how much sugar the shop was allowed to buy. However, supplies were not guaranteed and still ran out very quickly.

In January 1918, rationing was introduced for butter and margarine and other products were gradually added. Sainsbury’s welcomed rationing as a fairer way to share out food in short supply but was frustrated at the imposition of fixed prices. The company was threatened with prosecution several times for selling goods at prices below those set by the Board of Trade.

Over the course of the war, trading hours were reduced and shops were given permission to close early if they sold out of goods. Long queues formed when deliveries of high demand goods were made. Short supply goods were described in coded ‘back slang’ (e.g. ‘nocab’ for bacon), to avoid uncontrollable behaviour. Ethel Jessop, manager of the Woodford branch, phoned the police when rioting broke out among workmen who could not buy cheese.

Profit margins were squeezed and cost increased. As a result, Sainsbury’s profits after tax fell from £119,306 in 1918 to £71,888 in 1919. Rationing ended in May 1919, but rising prices meant it was soon reintroduced for meat, butter and sugar. It was not until the financial year 1920-21 that food retail was freed from restrictions and Sainsbury’s profits returned to their former levels.

Communication and distribution

Preparations for food rationing during the Second World War began in November 1936 when the Ministry of Food was set up as part of the Board of Trade. Registration began in November 1939 and food ration books were issued to every man, women and child in January 1940.

The Ministry of Food set up local food offices to license food dealers, distribute ration books and implement government regulations. Sainsbury's set up its own rationing department at its London head office.

The Ministry of Food's regulations were communicated within Sainsbury’s through a new network of 'contact clerks'. The clerks telephoned selected branches as soon as they had been notified by the Ministry of a change in the system. These branches were then responsible for passing the messages on to a further group of shops in their area.

This 'contact clerk' system was so efficient that some local food officers believed that Sainsbury's had prior knowledge of the regulations issued by the Ministry. Many local food offices discovered that it was quicker to telephone Sainsbury's rationing office for information than go through their own complicated official channels.

Sainsbury’s central depot at Blackfriars was vulnerable to enemy air attack, so temporary regional depots were established at Bramshott in Hampshire, Saffron Walden in Essex, Fleckney near Leicester, and Woolmer Green in Hertfordshire. Decentralisation also saved on fuel and enabled Sainsbury’s to distribute food to its branches across the country while still complying with wartime restrictions on the movement of foodstuffs.

Registration for rationing

At the beginning of November 1939 families were instructed by the Ministry of Food to register with a retailer as a preliminary to the introduction of rationing.

As registration committed a customer to using a particular shop, Sainsbury's was anxious to obtain as many registrations as possible. However, staff were instructed not to 'tout' for registrations. Instead they were told to rely on Sainsbury's reputation for quality and hygiene.

The paperwork involved in each registration was complex. Separate counterfoils had to be detached from the customer's ration book for every member of each family. These had to be checked, sorted into alphabetical order, collated and despatched to the local food office.

For most of the duration of the war customers were required to re-register twice a year. Sainsbury's was particularly vulnerable if customers transferred their registrations to other retailers as the majority of its business came from the sale of rationed goods such as bacon and dairy produce.

William Guest, manager of the branch at 66 Watney Street, was inundated with customers who were unable to fill in their ration books. This caused the staff at the small branch so much additional work that he applied to the district supervisor for help. William recalled:

‘The very next day a taxi drew up outside and out stepped Miss Potter and a group of her clerical staff. They loaded the ration books into the taxi and took them to Blackfriars, returning 24 hours later with a perfectly ordered filing system and several thousand ration books immaculately filled in.’

Rationed goods

The system was extremely complex as products were rationed at different times and in different ways. Butter, bacon and sugar were the first goods to be rationed in January 1940. They were followed by meat and preserves in March 1940, tea, margarine and cooking fats in July 1940 and cheese in 1941.

Sugar, bacon, butter, cheese and cooking fats were rationed by weight. Jam and other preserves were rationed as a group so that customers could choose whether to buy jam, marmalade or syrup. At some points in the war they could 'swap' the jam ration for extra sugar. To complicate matters further an individual's entitlement varied according to the food supply and their occupation. The distribution of a number of important foods such as milk, eggs and oranges was controlled to ensure that special allowances could be made for expectant mothers, babies and the elderly.

Breaking government regulations would jeopardise Sainsbury’s rights to trade. Despite pressure from customers, compromises on rationing were strictly forbidden. In 1943, when a store manager was fired for stealing rationed goods, the General Manager wrote ‘we find it hard indeed to think of a more despicable act'.

Rationing continued long after the end of the war. In December 1948 jams and preserves were the first products to be taken off the ration. Milk was not decontrolled until January 1950. Tea was de-rationed in October 1952, sweets in February 1953, sugar and eggs during the autumn of 1953, and butter, margarines and cheese seven months later. It was not until bacon and meat came off the ration on 3rd July 1954 that wartime restrictions finally ended.

Fair Shares scheme

Sainsbury's responded to wartime trading difficulties by emphasising its traditional strengths. Press advertisements stressed the choice of goods to be found in a Sainsbury's store. Customers were reminded that a trip to Sainsbury's was more convenient than visiting half a dozen specialist shops during the blackouts.

Sainsbury's also introduced a 'Fair Shares' scheme to ensure that goods in short supply - such as sausages, cake, meat pies, blancmanges and custard powder - were distributed evenly. Customers were allocated a number of points, according to the number of rationed goods for which they were registered. The scheme encouraged customers to register for all rationed goods at Sainsbury's.

To promote the use of the points system a series of advertisements were created (by Francis Meynell who also produced the government's ‘Food facts’ advertisements), suggesting meal ideas using ‘points’ foods. The scheme was noted by the Ministry of Food. On 1 December 1941 the government introduced its own ‘points’ scheme covering a wide range of grocery lines.

Customer service

Despite the 'Fair Shares' scheme, many customers became frustrated at the long queues that formed for un-rationed items. As Sainsbury’s daily staff bulletin put it: ‘The knack of keeping happy those customers who are waiting is one of the greatest gifts which a saleswoman can possess’.

To ease the situation Sainsbury's developed a system known as 'call backs'. This enabled a customer to leave her shopping list at the store and call back later to collect her purchases. Priority was given to working people who had less time to do their shopping. In areas where there were large numbers of factory workers, Sainsbury's made arrangements for stores to remain open late one evening a week so that workers could collect their orders.

Sainsbury’s strived to keep a balance between wartime cutbacks and maintaining high levels of customer service. Against suggestions that cutting home delivery would save fuel, the company kept up the service for those most in need, such as their elderly or ill customers.

Air raid trading

The only damage recorded to a Sainsbury’s store because of the First World War air raids was in Streatham. The shop at 168 High Road was bombed by a Zeppelin in 1916.

When the Second World War was declared in September 1939, air raid procedures were immediately sent to branch managers. Staff were instructed to close their shops during an air raid and direct customers to the nearest ARP shelter. In reality many customers stayed on the premises, sheltering in the basement on benches made from egg stall boards. Where no basement was available, it was suggested that ‘quite good cover is to be had beneath the counter or the back shelf’.

At the height of the Blitz, daytime raids had become so common that Sainsbury’s shops could continue trading at the discretion of the manager. Where shops remained open during an air raid, staff with whistles were positioned at door as ‘spotters’. Members of staff often displayed great determination, despite the raids. A customer at Walthamstow recalled queuing up outside the wrecked shop after a bad night of bombing, to find that the elderly manager had been there since 2am, ‘dusting the bacon and scraping soot etc. off the margarine’.

Second World War, The London Blitz

Over the course of the war there were around 600 incidents of bomb damage to Sainsbury's stores.

The garage workshops, ‘kitchens’ and bacon stoves at the Blackfriars headquarters were also damaged. Sainsbury’s bacon stoves at Union Street were being used by the Ministry of Food to store fresh meat. Upon hearing the news of a direct hit to this building, Robert Sainsbury is reputed to have hitched a lift to the premises from a passing fire engine.

Four members of staff at the Marylebone branch were killed during a night raid on 19 September 1940 and it took five hours to rescue the other members of staff from the debris. Many of the London shops suffered damage on a smaller scale but were able to continue trading.

London’s East End was particularly badly hit during the air raids and the branch at 66 Watney Street had to be closed when an unexploded bomb crashed through the wall of the adjacent Maypole Dairy. For several days, the shop traded from a stall set up on the street, with food delivered and collected daily by van.

Sainsbury’s created a contingency plan in case of an enemy invasion. Branches within 30 miles of the coast received detailed instructions. Managers were told to requisition a branch van and take cash and valuables to an alternative branch or depot.

The instructions stated: ‘If transport is commandeered, you must do your best to persuade the powers that be of the necessity of keeping your own transport to move goods from the shop which would be of value to the enemy. If the roads are blocked you must use your own initiative.’

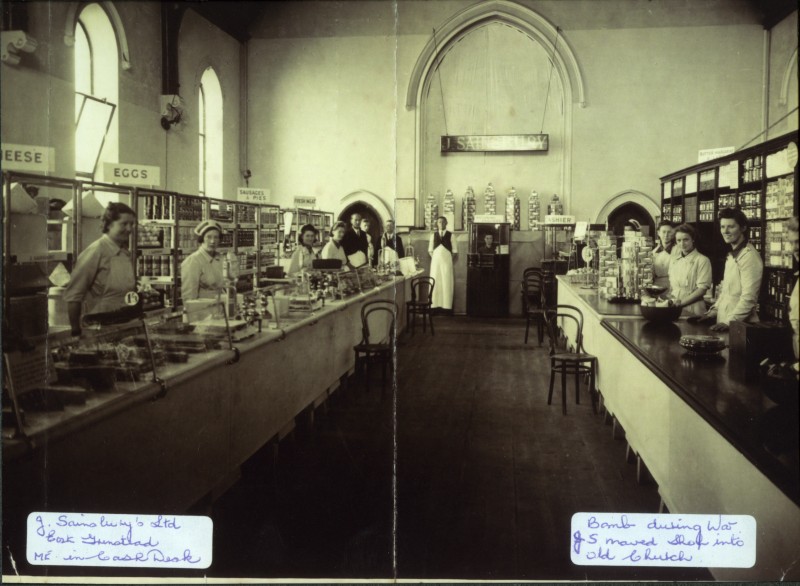

East Grinstead ‘shop in a church’

On 9 July 1943 an enemy aircraft bombed and opened fire upon several buildings in the High Street, including the cinema and an ironmonger’s shop with 500 gallons of paraffin in its basement store.

The fuel exploded and the blast swept through the parade of shops, causing the rear of Sainsbury's branch at 37-39 London Road to collapse. The final casualties numbered 108 killed and 235 injured, one of the highest civilian losses in the country. The Sainsbury’s shop had not been destroyed, but it was unsafe to enter. For six weeks, Sainsbury’s traded from a temporary shop inside a disused Wesleyan Chapel in London Road. A year later, on 12 July 1944 the shop was completely destroyed by a V1 bomb. A delivery van from Blackfriars was supplied and fitted out as a travelling shop, complete with weights, scales and counters. The emergency shop served customers while the disused chapel was refitted as a Sainsbury's shop. This 'shop in a church' continued to trade until 1951 when a new self-service store was opened.

Related content

-

Newspaper advertisement to ask customers to register name and address in order to receive regular suppiles of butter and margarine.

"Register with Sainsbury's" newspaper advertisement proof

SA/MARK/ADV/1/1/1/1/1/6/7/21

-

'Let's be frank about this Rationing and Registering!' advert, 1939 encouraging customers to register their ration books quickly. Includes five points about rationing. Includes a pencilled note that it was placed in the Star on 14 Nov 1939.

"Let's be frank about this Rationing and Registering!" newspaper advertisement

SA/MARK/ADV/1/1/1/1/1/6/20/7

-

Image showing: Flaked Oats Scotch (Sainsbury); Macaroni (Sainsbury); Sunland marmalade; Selsa Fish Paste Sardine & Tomato & Other Fish; Swift Veal Loaf; and a ration book for 1947-1948 issued to J.L. Woods [Jim Woods, a senior manager at Sainsbury's responsible for publicity, advertising etc]. Selsa was a Sainsbury's own-brand used for various products.

Image of flaked oats, macaroni and other products with a ration book

SA/PKC/PRO/3/1/3

-

Leaflet relating to the J. Sainsbury Ration Cards which limited the amount of certain non-rationed goods that each customer could buy.

"Sainsbury's scheme for the fair distribution of certain 'short supply' foods" leaflet

SA/WAR/2/2/1

-

The photograph shows a Sainsbury's emergency shop set up outside a bombed building. It was one of two vans used to serve customers when a Sainsbury's branch was unable to trade normally following bombing. This photograph appears in 'The Best Butter in the World' page 121.

Photograph of emergency shop

SA/WAR/2/IMA/1/10

-

This branch was temporarily moved into a disused church after a bomb hit the shop building during the Second World War.

Photograph of interior of East Grinstead shop in church with staff, Second World War

SA/WAR/2/2/2

Related memories

Do you have an image that relates to this record? Add your personal

touch. If you worked for Sainsbury’s, please provide brief career details

and include dates where appropriate.

Comments

Comments (0)